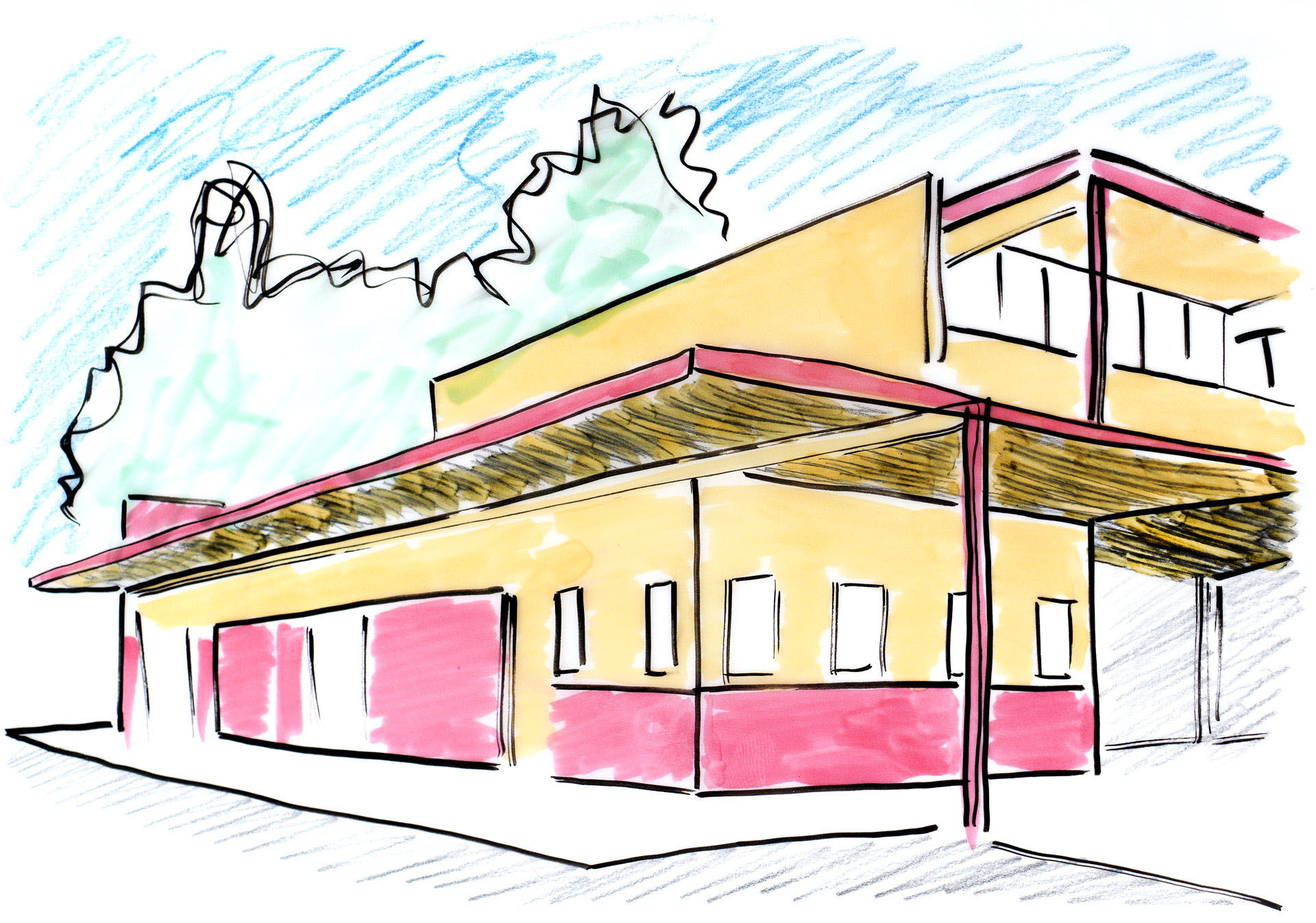

Neutra’s Basketball Court

Richard Neutra • 1953 • Eagle Rock, California

Sigma fp L • Rokinon 24mm f/3.5

809 words • 8 images

We must’ve been looking for a place to walk our neurotic dog. I can’t think of any other reason why we would’ve ended up at the Eagle Rock Rec Center in 2016, to take a walk on the big field that stretches out below the building pictured above. I must’ve wondered who designed the building, since I’ve known Neutra designed it for as long as I’ve known about the building, but back then — when “Neutra” was just a name I remembered from an architectural history survey course — it wouldn’t have meant much.

What struck me then was how dilapidated the whole thing was. Crumbling concrete, peeling paint. Not tragically dilapted, just… kind of cruddy, in an oddly exciting way. Here was an architect mentioned in every 20th century architectural history textbook you can find, and yet, here was an incredibly normal building that people played basketball in. No fences, no guards, no tickets. Just a Neutra, next to some tennis courts, above a baseball field.

•••

What I didn’t known then was how prolific Neutra was in Greater Los Angeles; scroll through this page on usmodernist.org to get a sense of his prolificness.

Since the 1980s, when apparently the city wanted to demolish the Clubhouse (built in 1953), there’s been an ongoing effort to preserve and restore it, though so far it doesn’t seem to have come to much.

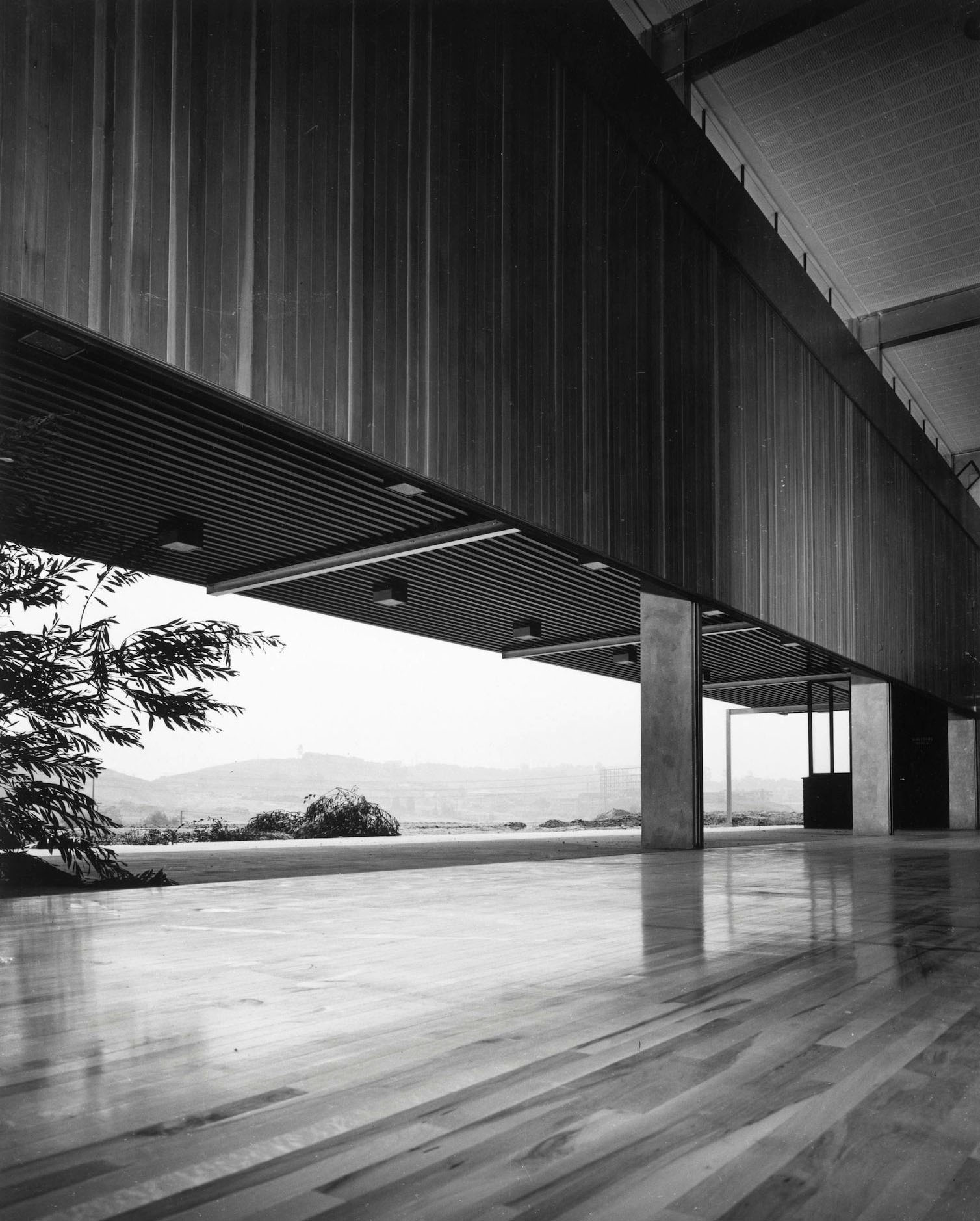

When Julius Shulman photographed the building, it was a much more striking design: on the southern and eastern elevations, a dramatic steel overhang — supported by a single steel column at one end and a masonry wall at the other — seemed to levitate above expansive planes of glass and retractable walls. In fact, the floating effect was so striking, years after the building’s opening, anxious city officials insisted that more steel columns be added to the eastern elevation to support the overhang. Today you can easily spot the imposter columns: Neutra’s minimal structural supports are always his signature “spider legs” that shoot, briefly, beyond the roofline, while the imposters meet it squarely.

From the view in Shulman’s photograph above, you can sympathize a little with the city officials, as it’s a little confusing what’s going on above you. The overhang is just a horizontal eave made of steel decking, but when you were standing on the basketball court floor and the retractable walls were hoisted up to let in the breeze, it looks quite a bit like a precarious cantilever. Not saying I think the city officials did the right thing, just that the drama of Neutra’s design was maybe a bit much for a basketball court.

If you were to experience the same view today, each of the horizontal steel beams would be met with a vertical steel column at the overhang’s edge. So… very much no longer cantilever-looking.

But to get to that view, you’d have to convince someone to draw up the retractable walls. And in 5 or 6 visits to the building over the past 8 years, I’ve never seen the walls retracted. Which makes sense.

Neutra seemed to love a building that could, in some way, move. Usually this came in the form of vertical louvers for sun-shading, a device featured prominently on his Los Angeles County Hall of Records, which has long aluminum louvers on its southwest side. But like most things that move on a building, one day they stopped moving. That is, they broke, and in breaking made a very good building very bad (as chronicled by Sam Bloch in this great article). It’s a similar story at Neutra’s own house, the VDL House in Silver Lake, where mechanical vertical louvers shield the bedroom views. Except they’re not mechanical anymore, they’re just permanently facing one direction.

I don’t actually know if the movable walls of the Clubhouse are broken, though they might as well be.1 Much of the rest of the design has been broken intentionally. The northern elevation still has its original signage — big, beautiful, dimensional letters reading “Eagle Rock Park” — but the rest is quite confusing: a blank, plywood-boarded wall overlooking an expanse of concrete below a huge grassy hill bounded by lovely brick walls. Why are there brick walls there?

As originally conceived, the plywood boards were gone and a stage was there in its place. The brick walls on the large grassy hill delimited seating for the outdoor amphitheater. The concrete pavement was a reflecting pool.

All in all, the Clubhouse was a beautiful, almost ethereal building when all of its glass and pools and moving walls were in place. These days it is still a fascinating structure, and I understand the community’s intermittent calls for a restoration of Neutra’s original design. But it is hard to imagine huge planes of glass or a reflecting pool being reinstalled in our hot, mosquito-infested Los Angeles.

-

To see some very cool movable walls from a very different warm climate, check out this video on Paul Rudolph’s Walker Guest House. ↩